CM608: The Antikythera Wreck was a Phoenician Ship --

and the Antikythera Mechanism was its GPS

David Noel

<davidn@aoi.com.au>

Ben Franklin Centre for Theoretical Research

PO Box 27, Subiaco, WA 6008, Australia.

PART ONE

The Story So Far

Antikythera

In the year 1900, a vessel belonging to Greek sponge divers encountered bad weather in the Mediterranean, and sheltered for a while against the tiny Greek island of Antikythera (Figure F1). In those days, synthetic plastic sponges had not been invented, so sponges used in toiletry and other things were natural sponges, harvested from the sea floor.

Figure CM608-F1. Location of Antikythera. From [1].

Antikythera lies between Crete and the southern parts of the Greek mainland. When the Greek sailors found the weather to have improved, they thought they might as well check the local waters for sponges before moving on.

One of the divers donned a traditional diving suit -- the sort made of heavy canvas, with a metal helmet, and connected by an air-pipe with an air-pump on deck -- and dived to the sea-floor, at a depth of about 40 metres. To his astonishment. he found the wreck of a large wooden ship, with its contents strewn over the sloping sea-floor.

Figure CM608-F2. Traditional diving suit. From [2].

These contents comprised a large number of marble and bronze statues, together with with ceramic and glass vessels, and including the large fired-clay jugs known as amphora, used to transport olive oil, wine, and other commodities in ancient times.

The find was reported to the Greek Government, who backed expeditions using larger ships during 1900-1901 to retrieve as much as possible from the site. As well as the statues and jugs, items of jewellery and coins were found, together with a corroded bronze plate.

Over the years since 1900, further on-site dives were made, and a huge amount of research done on items retrieved from the wreck. All this work is summarized in a 2012 publication of Greece's National Archaeological Museum, entitled "The Antikythera Shipwreck: the ship, the treasures, the mechanism" [3].

This tremendous book includes a wealth of photographs and detailed descriptions of samples of all the hundreds of articles retrieved from the wreck, together with discussions of their likely origin, and the circumstances of the period when the ship was wrecked -- dated to approximately 65 BC. It is credibly believed that the ship was headed for Rome, and was loaded with items intended to decorate the villas of rich Romans.

Retrieval of items from the wreck continues to the present day, with a major 1976 expedition mounted by Jaques Cousteau in collaboration with the Greek Institute of Marine Archeology [5]. A report from 2016 [4] gives a recent update.

"One of the world's most storied shipwrecks is still yielding new discoveries.

More than 60 artifacts were pulled from the famed Antikythera shipwreck during a recent expedition of the vessel, which sank in the Aegean Sea in approximately 65 BC.

The expedition by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) found gold jewelry, glassware, the spear from a statue, marble sculptures and decanters in the past few weeks.

One of the more curious finds appeared to be an ancient weapon known as a dolphin. The object is a lead and iron artifact that weighs about 220 pounds. Dolphins were defensive weapons that were dropped from the ship's yard -- a spar on the mast -- onto the deck of an attacking ship, such as a pirate vessel.

The shipwreck, discovered in 1900 by sponge divers, was most known for the Antikythera Mechanism, an ancient device that in some ways may have been the world's first computer. The clock-like gadget with interlocking gears was believed to have been used to help predict eclipses and the positions of celestial bodies."

PART TWO

The Antikythera Mechanism

When the hoard of items recovered from the Antikythera wreck were taken back to the museum site in Athens, curation of the objects for possibly display took some time.

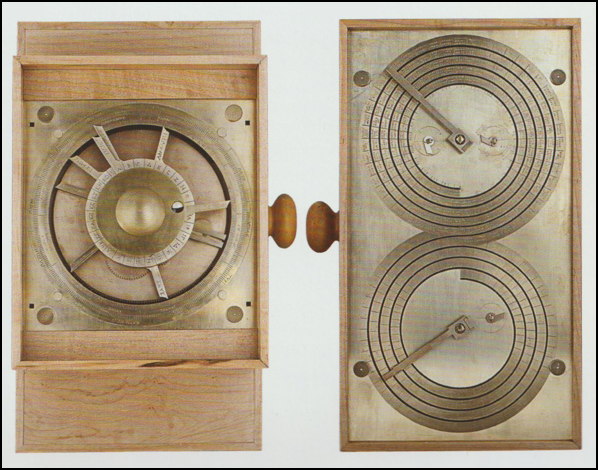

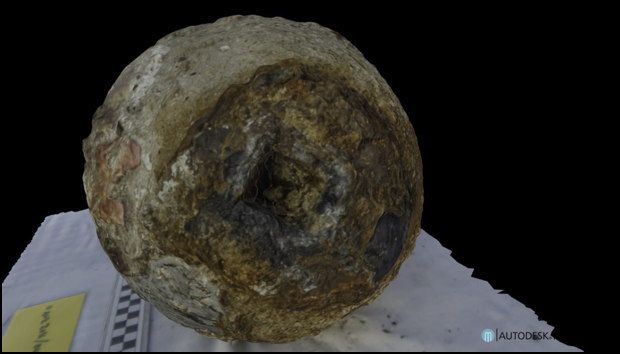

The corroded bronze plate mentioned above was not even looked at for some months. When it was eventually looked at, it had become split into three or four fragments. The main part (Figure F3) looks like a wheel with two cross-bars. The diameter of the wheel is about 13 centimetres (5 inches).

Figure CM608-F3. One fragment of the Antikythera Mechanism. From [5].

Credit for first noticing that the bronze plate appeared to contain a number of complex gears is usually attributed to Spyridon Stais, who had been Greece's

Minister for Education, and one of the project's original supporters. This was during a chance visit to the museum with his wife, on a Saturday morning [5].

Such a device, comparable in complexity to a modern alarm clock, immediately raised enormous questions about its age and origins. At the time, the earliest known other devices with gears were dated more than a thousand years later, with the geared astrolabes of the 1200s [6].

Since then another geared device has come to light, a "sundial calendar" found near Beirut, Lebanon, and tentatively dated to 500 AD [7]. This had only four gears, much simply than the Antikythera Mechanism -- but yet it shows knowledge of gearing had not been completely lost.

A suggestion that the Mechanism was of much later construction than the ship, and happened to have been dropped among the ship's items at a later date, was soon discounted. With further investigation (such as with dated coins found in the salvage), the date when the wreck occurred was narrowed down to about 65 BC.

The ship itself was estimated to have been built up to a hundred years previously, with the Mechanism build dated at possibly between 170 and 70 BC.

Over the years since 1901, continuing scientific studies have revealed more and more details of the astonishing complexity of the Mechanism. Starting in the 1950s, the British physicist Derek De Solla Price spent many years working out what the Mechanism did and what it was for, publishing the results under the title "Gears From The Greeks" in 1974 [1]. Price was able to use x-rays of the device fragments to locate and quantify some of the gear positions and their tooth numbers.

Price was totally impressed with the advanced nature of the Antikythera Mechanism, which appeared to be more than a thousand years ahead of its time. He wrote "Its discovery 55 years ago ... was as spectacular as if the opening of Tutankhamen's tomb had revealed the decayed but recognisable parts of an internal combustion engine" [7].

Following Price, Michael Wright, a curator at London's Science Museum, toiled for years (in his own time and at his own expense) to work out more about what the device did and how. He and his co-worker Jennifer Field discovered that it had contained epicyclic gears -- gears mounted upon other gears.

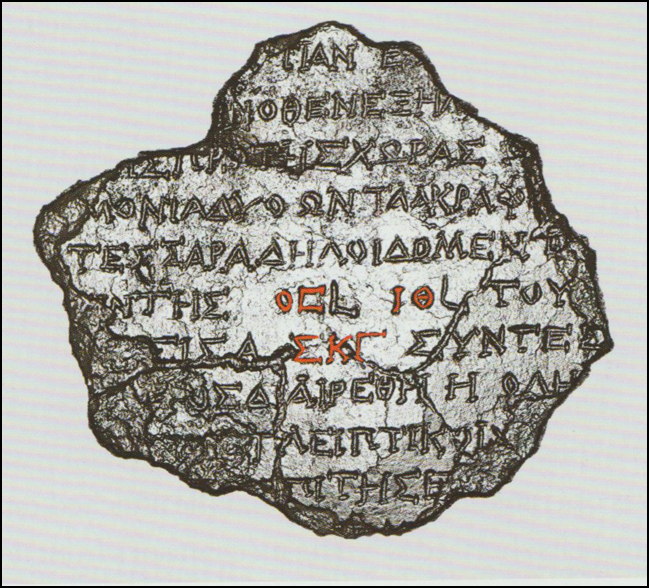

Since then, newer scientific methods and instruments continue to reveal more. On the original examination, it was noted that parts of the device were inscribed with Greek characters. In 2005, advanced computerized tomography methods (CaT Scans), borrowed from medicinal uses, were able to reveal more and more details, including the presence of several thousand Greek characters.

This more recent work was done by a team led by Tony Freeth. A special scanning machine, weighing 8 tons, was transported to Athens to scan the mechanism's fragments.

Figure CM608-F4. Greek characters revealed by CT Scans. From [3].

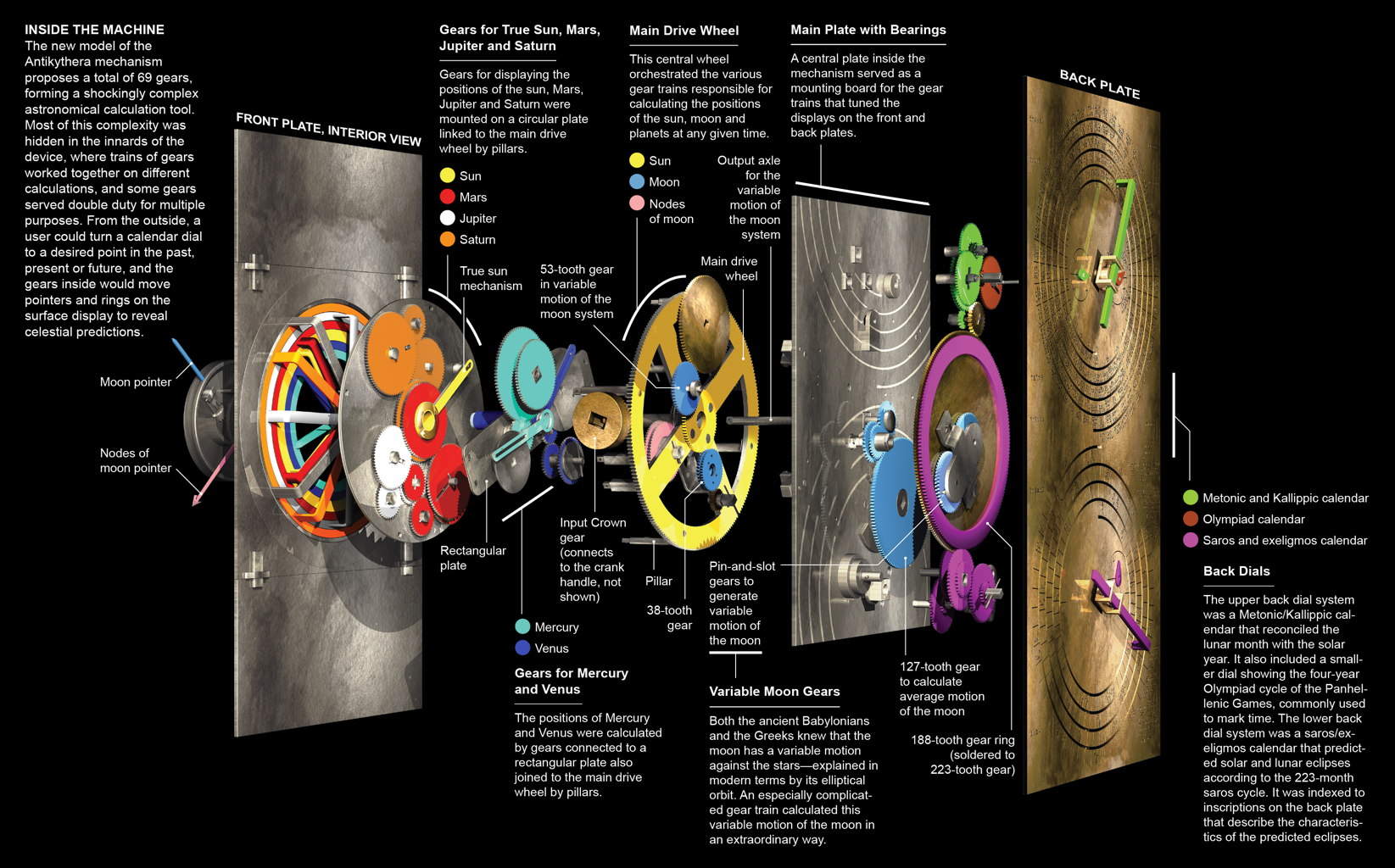

These characters form words and labels of astronomical terms, and clearly refer to movements of the sun, moon, and the five planets known to the Greeks, as they move through the zodiac. Some passages give instructions on using the device.

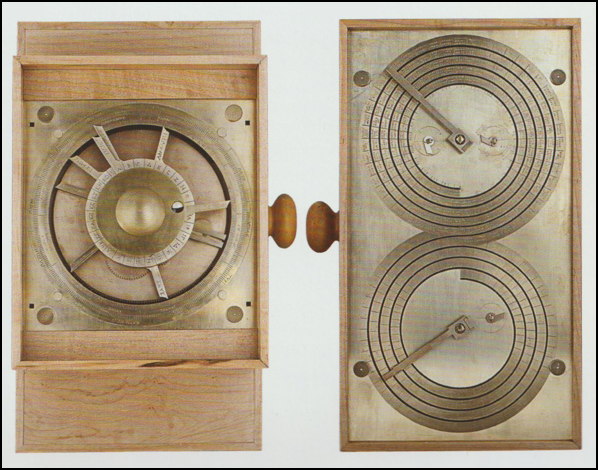

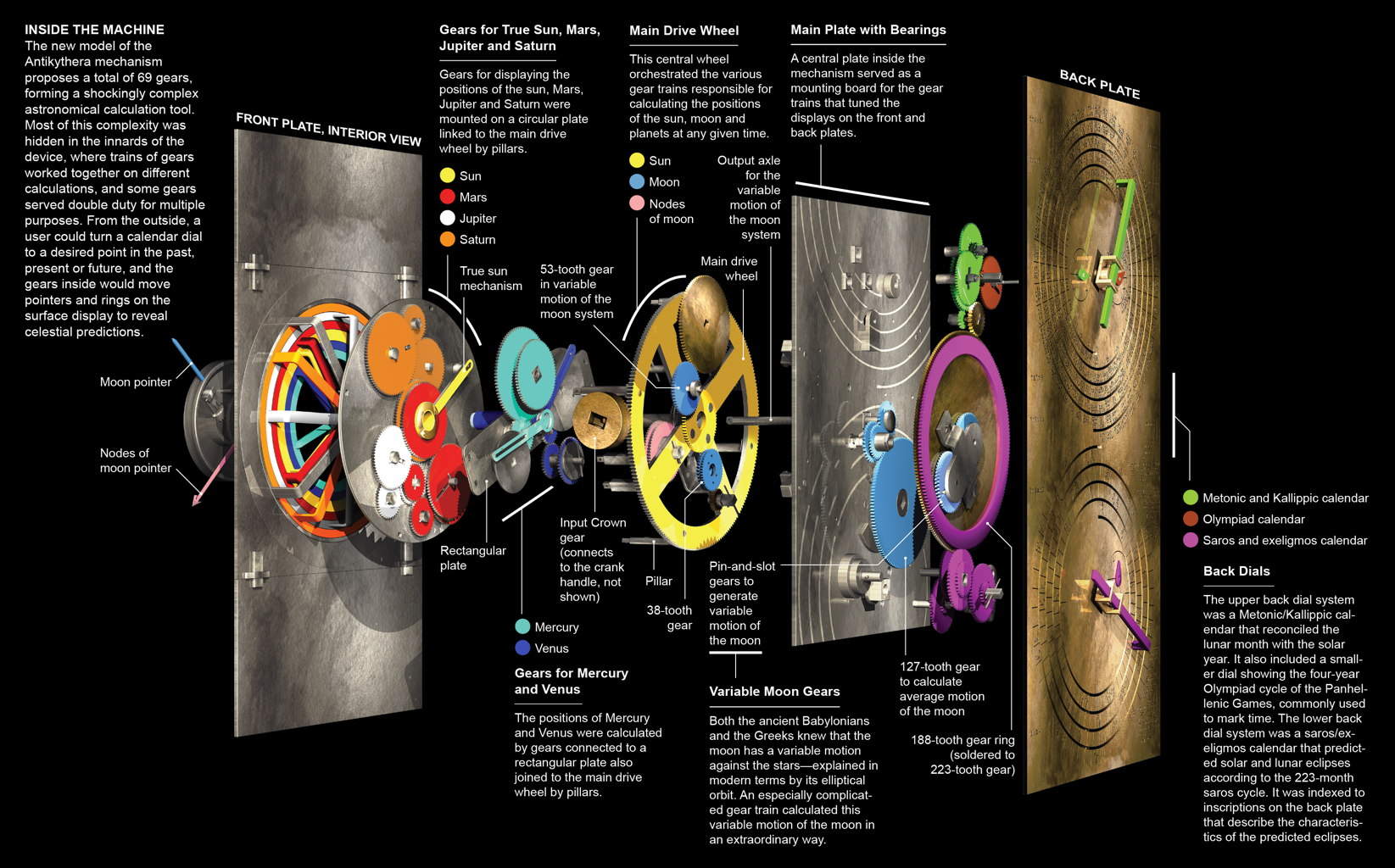

The mechanism contained at least 39 gears, and possibly had held as many as 69 (some pieces have been lost). It had been contained in a wooden case, with a handle on one side -- of similar size to a thick book. Some of the rear wheels referred to dates of the Olympic and other games which followed four-year cycles. Other discs were annotated with dates in the Egyptian and other calendars.

Figure CM608-F5. Michael Wright's reconstruction of the Antikythera Mechanism. Front shown on left, rear on right. From [3].

Continuing research and calculations show that the Mechanism is considerably more complex and more powerful than even Derek Price had considered. Following is a recent schematic or reconstruction of how the Mechanism is believed to have been made.

Figure CM608-F6. Schematic of the Antikythera Mechanism's purported construction. From [9].

What did the Antikythera Mechanism do?

There is no doubt that the Mechanism models the apparent movements of the Sun, the Moon, the planets, and the stars. Moving the components of the Mechanism (its gears, pointers, scales, connectors, and graduation points) gives a very accurate reflection of what could be observed from the actual celestial sphere, so it could predict eclipses, indicate when night or day would fall, and give the positions of planets at a given time.

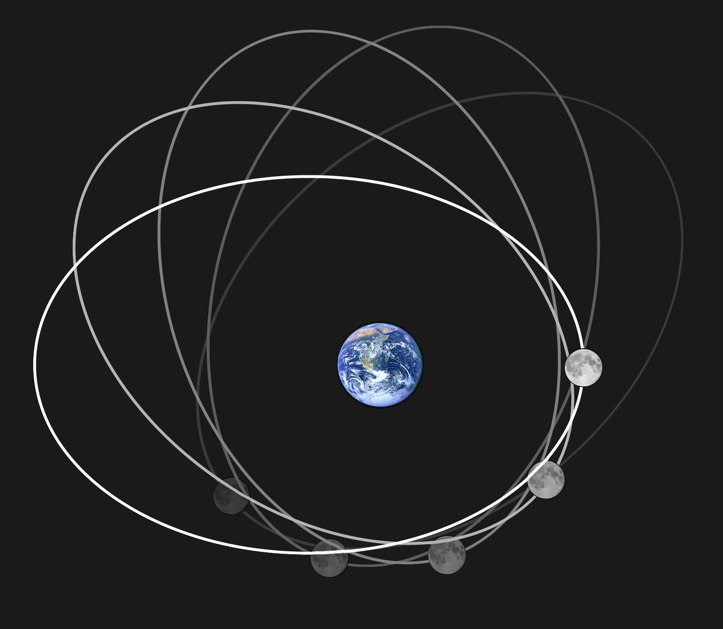

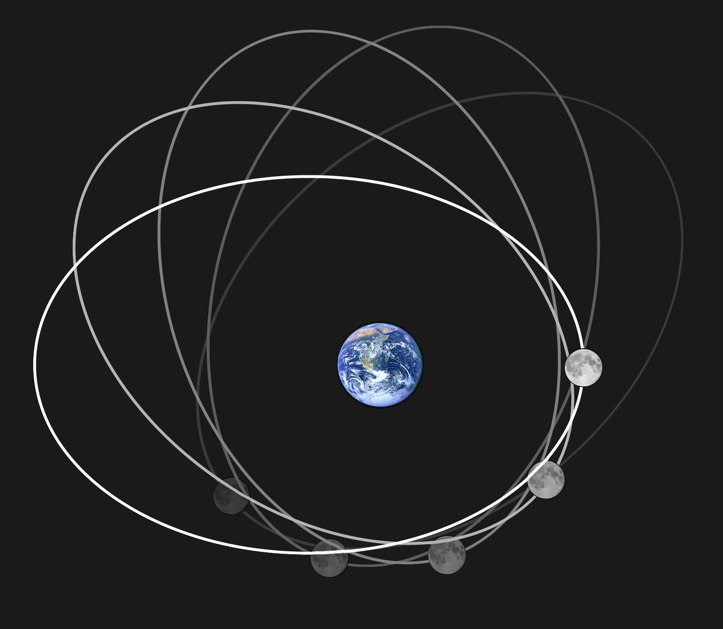

An indication of its remarkable accuracy concerns precession of the Moon. Our Moon moves around the Earth, not in a circle, but in an ellipse, an oval path with a large axis and a small one (Figure 7).

Figure CM608-F7. Precession of the Moon's orbit. From [11].

This ellipse is not fixed in space, but moves slowly around in its inclination to the Earth (it "precesses"), taking about 9 years to come back round to a given orientation. Surprisingly, this fact has been known since antiquity.

The point here is, that the Mechanism includes a sophisticated method of allowing for this subtle variation in the position of the Moon.

Here is a recent (2022) summary of the position, from Tony Freeth's article [10].

"The ancient Greek astronomical calculating machine, known as the Antikythera Mechanism, predicted eclipses, based on the 223-lunar month Saros cycle. Eclipses are indicated on a four-turn spiral Saros Dial by glyphs, which describe type and time of eclipse and include alphabetical index letters, referring to solar eclipse inscriptions. These include Index Letter Groups, describing shared eclipse characteristics.

The grouping and ordering of the index letters, the organization of the inscriptions and the eclipse times have previously been unsolved. A new reading and interpretation of data from the back plate of the Antikythera Mechanism, including the glyphs, the index letters and the eclipse inscriptions, has resulted in substantial changes to previously published work.

Based on these new readings, two arithmetical models are presented here that explain the complete eclipse prediction scheme. The first model solves the glyph distribution, the grouping and anomalous ordering of the index letters and the structure of the inscriptions. It also implies the existence of lost lunar eclipse inscriptions.

The second model closely matches the glyph times and explains the four-turn spiral of the Saros Dial. Together, these models imply a surprisingly early epoch for the Antikythera Mechanism. The ancient Greeks built a machine that can predict, for many years ahead, not only eclipses but also a remarkable array of their characteristics, such as directions of obscuration, magnitude, colour, angular diameter of the Moon, relationship with the Moon's node and eclipse time. It was not entirely accurate, but it was an astonishing achievement for its era."

PART THREE

What We Know and What We Don't Know

Under the title "A Model of the Cosmos in the ancient Greek Antikythera Mechanism" [8], Tony Freeth summarizes his view of the device.

"The Antikythera Mechanism, an ancient Greek astronomical calculator, has challenged researchers since its discovery in 1901. Now split into 82 fragments, only a third of the original survives, including 30 corroded bronze gearwheels. Microfocus X-ray Computed Tomography (X-ray CT), in 2005 decoded the structure of the rear of the machine, but the front remained largely unresolved.

X-ray CT also revealed inscriptions describing the motions of the Sun, Moon and all five planets known in antiquity and how they were displayed at the front as an ancient Greek Cosmos. Inscriptions specifying complex planetary periods forced new thinking on the mechanization of this Cosmos, but no previous reconstruction has come close to matching the data.

Our discoveries lead to a new model, satisfying and explaining the evidence. Solving this complex 3D puzzle reveals a creation of genius -- combining cycles from Babylonian astronomy, mathematics from Plato's Academy, and ancient Greek astronomical theories."

Freeth's view of the device as "an ancient Greek astronomical calculator" is a common one, and very understandable. But the present perception of it leaves a number of serious question without entirely satisfactory answers. Here are some of them.

Question One. Who made the device?

Question Two. What was it used for?

Question Three. Why was it not mentioned in writings of the time?

Question Four. Why was it never developed further?

The answers to these questions are presented here. They do not rely on any new evidence, but on a new look at existing evidence, from a different perspective.

Briefly, the answers say that Antikythera-type devices were developed by the Phoenicians, and used on their ships as GPS devices, to determine their exact positions at sea.

Proposition CM608-P1.

PART FOUR

The Phoenicians

In spite of their position as an advanced, sophisticated, and long-lasting civilization, the Phoenicians are surprisingly poorly known, in comparison with other civilizations such as the Babylonians, the Greeks, and the Romans.

There are a number of reasons why the Phoenicians have tended to exist in the background of history, rather than centre-stage. Firstly, they never existed as a typical empire, with a recognizable capital, situated within obvious boundaries.

Secondly, they never possessed a clear name, by which they were known throughout their history, in contrast to the empires just mentioned. The Keftiu, the Canaanites, the Minoans, the Carthaginians, and the Punic people were just some of the names applied to the Phoenicians by outsiders. Apparently, the Phoenicians generally called themselves after their local town or city -- Tyrians from Tyre, Sidonites from Sidon, and so on.

Thirdly, their civilization was very different in nature from one like the Romans. They were essentially nautical trading people, who lived on the sea and on home ports situated on islands just off coastal areas, on peninsulas, or on coasts backed by tall mountains -- all places where their front doors were on the sea, and their back doors readily defensible.

The people we call the Phoenicians had their origins as far back as 6000 BC, or even earlier, at seafront settlements such as Byblos, in Lebanon -- about 30 km north of modern Beirut [12]. From there they spread to other cities on the Mediterranean coast, to Sidon, and to Tyre (which became their most important site in their early history).

Behind their cities lay the Lebanon Mountains, home to the famed Cedar of Lebanon, a valuable timber species. This formed the first of the Phoenicians' commercial industries. History records the logs going to the Egyptian pharaohs for building palaces and such (Egypt had little native large timber), and of course the Bible's King Solomon is recorded as using Phoenician cedar and artisans in building his Temple.

Figure CM608-F8. Lebanon and the eastern Mediterranean.

Quite early on. the Phoenicians worked out how to build excellent ships (they invented ship keels), and became famous as master traders and navigators, working all over the then known world, and beyond. A really excellent book, source of much of what is explained here, is Sanford Holst's "Phoenician Secrets" [13].

So, for much of their existence, the Phoenicians were the GoTo people, the suppliers of whatever you wanted (and could pay for), a combination of present-day Amazon, DHL, and Aldi -- what we could call the Amdaldi model.

Bearing this model in mind gives an insight into how the Phoenicians fitted into the wider world. Interacting with the Greeks, you could expect a belief in democracy, science, logic, and explanations of the world. Interacting with the Romans, you could expect conquest, exploitation, and good engineering and water supply.

With an Amdaldi entity, you could expect excellent availability of goods and services, with an unobtrusive supplier slowly establishing a growing representation within your community, and perhaps budding off and propagating in other communities. So you get a better idea of what the Phoenicians could be to you, by looking at them as a multi-national corporation, rather than as a rival nation.

Throughout their existence, the Phoenicians almost invariably adopted a policy of fitting in, of adjusting, of tolerance, towards their neighbours. Sanford Holst [13] gives many examples of this policy. When setting up what you could think of as a new Branch Office or Fulfilment Centre, they would go along with whatever their new neighbours preferred as much as they could, honouring their gods, giving them gifts and aid, and trying to be good citizens of their area.

If an aggressive army was approaching their city, they would send out gifts and welcomes, and even accept a position of apparent subservience to a greater power, paying tribute and waiting for that greater power to decay, as it eventually always would.

If the attacker would not accept their offers but insisted on complete control of their lives, the Phoenicians would resist for a while (they were in good siege positions on their offshore islands), and sometimes the threat would collapse.

If their position looked to be hopeless, a fleet of Phoenician ships would come into port, and the entire population would embark, taking their possessions with them, and distribute themselves among other Phoenician cities. All their records (presumably in the Phoenician language) would be taken with them or destroyed.

Left with an empty city, and no source of tribute or slaves, the attacker would often depart in disgust, when the original inhabitants would return and restore their city to its function. According to Holst, a likely origin of the term "Phoenician" is from this Phoenix-like behaviour of their cities, arising anew from their ashes.

As part of their policy of fitting in, the Phoenicians were happy to let the outside world look at them as if their attributes and names were typical. The head of the Phoenician city who cooperated with King Solomon in the temple build didn't mind being called King Hiram, but in reality he was more like the CEO of Phoenix Corporation (Canaan) Ltd.

In many of their settlements (read: Branch Offices), the Phoenicians built huge structures containing several hundred rooms, as at Knossos in Minoan Crete, and these are conventionally called Palaces. But these giant buildings were more like Fulfilment Centres, with workshops for making and treatment of goods, and extensive storage and shipping facilities.

The Palace at Knossos did contain a Throne Room, but this was fairly small and unimpressive. The thought arises that this might have been a "prop" Reception Lounge, where the "King" could entertain and chat with visiting heads of other countries, with enough pomp to make them feel comfortable..

About Aldi

According to Wikipedia [14], Aldi is the common company brand name of two German multinational family-owned discount supermarket chains, operating over 13,000 stores in 18 countries. The chain was founded by brothers Karl and Theo Albrecht in 1946, when they took over their mother's store in Essen. The business was split into two separate groups in 1960, that later became Aldi Nord, headquartered in Essen, and Aldi Sued, headquartered in Muelheim.

Since then, Aldi operations have extended selectively into 18 countries, including China, the USA, and Australia, as well as the UK and many other European countries.

Figure CM608-F9. Operations of Aldi as at 2024. From [14].

The table summarizes the 2024 position. Currently Aldi have over 13,000 stores worldwide, under their own name and a few other chain-store names. Each local group has a high degree of autonomy, and may have its own characteristics (for example, in Australia credit cards are accepted for payment, but with a surcharge).

So the total Aldi complex operates as a loose conglomeration of companies, each of which has its own board of directors, who set local policies. Suppose the urge arose to set up an Aldi chain in another country, such as Bulgaria -- part of the European Union, but with its own currency (and a non-Roman script).

Almost certainly those wishing to introduce Aldi to Bulgaria would set up a new limited company incorporated under Bulgarian law, and work with the other Aldi companies regarding supply of various grocery lines -- each Aldi offers a very wide range of goods drawn from worldwide sources.

Aldi owns hundreds of its own brand names, such as "Bramwells", which may be applied to a product such as peanut butter, in whatever store it is sold. Although German-based, many of their goods are labelled in English (even in China), although local labelling laws may affect this. Perishable items such as fresh fruit are usually locally sourced.

The point of all this is to comment that Phoenician "colonies" were largely set up in a similar way to a new Aldi branch in a new country. There was no central authority, such as existed in Rome, no-one issuing decrees to take effect throughout all an empire's possessions.

The Greeks are said to have invented democracy, and this was adopted in the earlier periods of Rome, with a standing Senate and officials chosen by election (although the range of those eligible to vote was limited). Democracy would not have been particularly evident in the Phoenician cities, any more than it is in Aldi or any other large commercial conglomerate today.

While the Greeks were justifiably proud of their science and scholarship, and published extensively about their activities and history and what they knew about the rest of the world, this was definitely not true of the Phoenicians. Yet the Phoenicians were very literate -- they invented the alphabet as we know it -- so it is a matter of what they let out to the outside world.

According to Bard AI, we know of thousands of works from ancient Greece. There are many complete plays, epic poems, philosophical treatises, and historical accounts that survive.

When asked about Phoenician literature, Bard AI gives a completely different picture. "We know the Phoenicians had a written language and literature thanks to references from other cultures. There are mentions of Phoenician writings like religious texts, practical documents, and even plays. The problem is, these original Phoenician works themselves are mostly lost. So, while we know they existed, giving a rough number of surviving works is difficult. There are some fragments and references, but no complete pieces".

Laws, Regulations, and Operating Manuals

The internal workings of a modern nation are described by its laws and regulations, with reporting and commentary by the media. These laws and regulations must, of necessity, be published and available for consultation. Some will contain explanations of the purposes and philosophies which underlie them.

This is not true for the operating manuals of a sprawling multinational conglomerate. Some will publish mission statements, and if they produce items used outside the organization, notes on these will be available to outsiders.

But much of what they document will be Company Confidential, or even Company Secret, stuff they would prefer outsiders not to know. Suppose a new and much more efficient or cheaper technique is developed within the company laboratories. In modern times, the first option open to them is to Patent the technique -- this means explaining its details in the Patent Office publications, but comes with the exclusive right to use the technique for a limited period, typically 20 years.

The second option is to keep the technique hidden, to maintain it as a Trade Secret. This is the option adopted by many commercial organizations, though of course we don't know the extent of this. The concept may not even be patentable, such as the current recipe for Coca-Cola.

Aldi will have their own operating philosophies and techniques for success, which they may want to keep to themselves. Some of the details may be guessed or worked out by outsiders, some not. Why is all the own-brand peanut butter sold by Aldi in Western Australia made in Argentina, where they don't even have stores?

In the same way, as master traders and navigators, the Phoenicians could have developed many trade secrets and techniques for themselves. So their practice of destroying or carrying away their records if they moved operations is very normal. And, in constant contact with other nations (their customers), it would be prudent not to write too openly about them.

The Minoans were amazingly ahead of their times

The story of the Phoenicians is a continuous one, spreading over 6000 years, but it can be split into three, according to what was their biggest city. In the first third, when building up their remarkable civilization, this major city (not really a "capital") was Tyre, on the eastern Mediterranean coast of modern Lebanon.

Tyre's period of predominance came to an end when besieged by Alexander the Great in 332 BC. After a seven-month siege, he conquered Tyre by building a massive causeway to bridge the gap between the mainland and the island city, allowing his forces to breach the walls. The city was then destroyed, and many of its inhabitants were massacred or sold into slavery.

However, well before this event, the Phoenicians had built up a major city at Knossos on the northern coast of Crete (near modern-day Heraklion). For a time, their CEO was "King" Minos, and it is said to be for this reason that Cretan Phoenicians are known as Minoans.

It is perhaps a coincidence that the Knossos site was first discovered by Minos Kalokairinos, a local businessman and amateur archaeologist, who, in 1878, was the first to unearth conclusive evidence of a large Bronze Age palace at Knossos. But the name best known for the Knossos discoveries was the Englishman Sir Arthur Evans.

From 1900 to 1905, Evans, who invested his entire personal wealth into the excavations, unearthed the largest archaeological site on Crete -- the undisputed ceremonial and political centre of Bronze Age Minoan civilization.

It is rather typical behaviour that the Phoenicians, when moving into Crete, did not "take over" the island. Instead, they set up a number of cities ("branch offices") in cooperation with the indigenous locals (who are said to have earlier migrated from the Danube area) in peaceful harmony.

The languages and scripts of pre-BC Crete are currently subjects of much research. The Phoenicians brought with their own alphabet, which was used to write their own language (this script was called "Linear B"),

For many years. the Linear B script remained undeciphered. But Michael Ventris cracked the code of Linear B in 1952. His work opened a window into a lost civilization and showed that Linear B was an early form of Greek, dating from about 1400 to 1200 BC.

As a boy, his fascination with the classics led Ventris to study Greek and Latin. Already a competent and zealous cryptographer at 14, in 1936 he heard Sir Arthur Evans lecture in London on the Linear B script that he had discovered at Knossos in about 1900, and how it still baffled linguists and archaeologists. Ventris' determination to solve the puzzle of this peculiar writing dated from that time [16].

This language apparently spread from Crete to the Mycenaeans on the southern Greek mainland, another Phoenician stronghold, later evolving into classical Greek. So the Greeks evidently owe both their language and their alphabet to the Phoenicians.

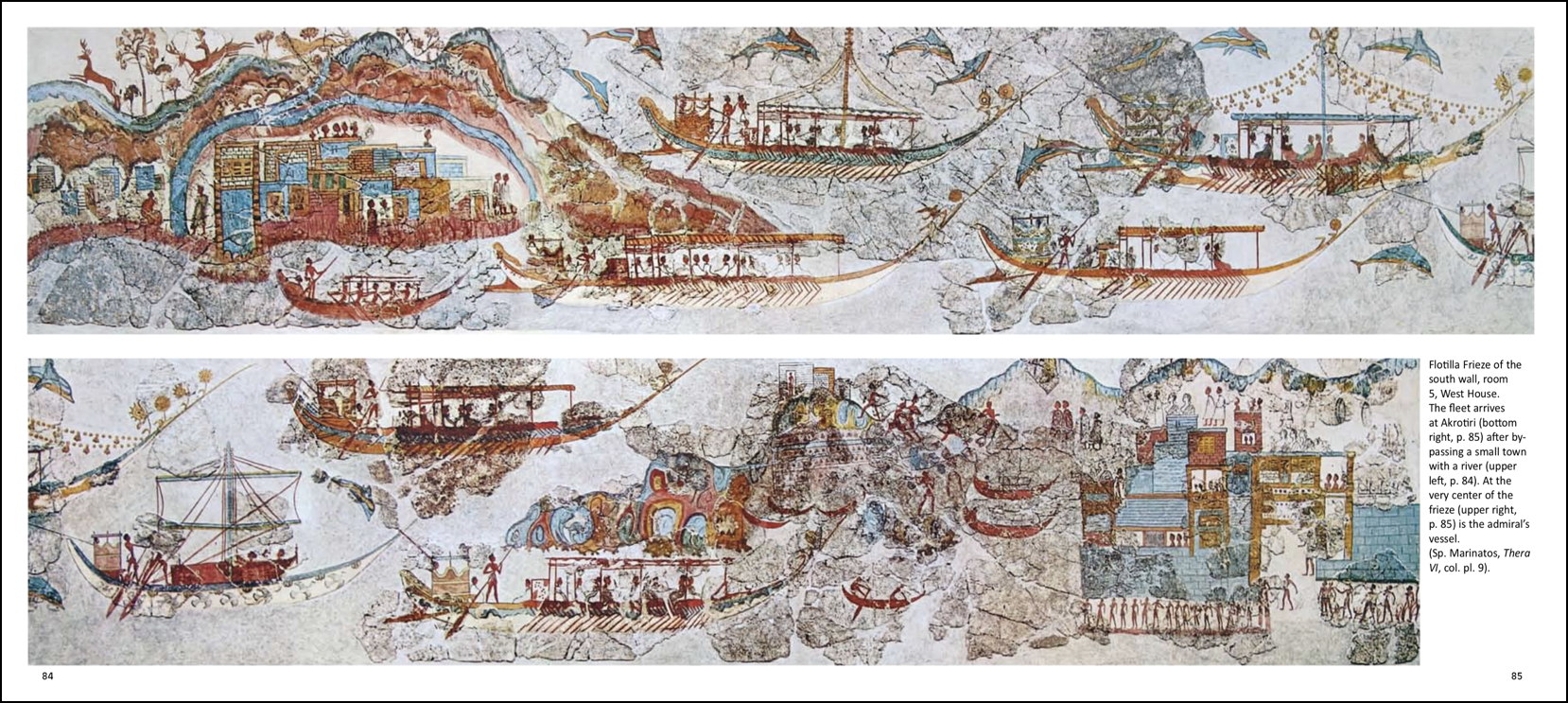

Knossos was the largest Phoenician city on Crete, but it ran in close accord with other Phoenician cities of its time, including Akrotiri. Akrotiri was situated on the small island of Thera (or in its Italian form, Santorini), about 150 km north of Knossos. The relationship between these two cities might have been like that between London and Bristol in modern UK -- two cities in regular touch and with very similar lifestyles.

So, around 1550 BC, Knossos was part of a remarkably advanced and sophisticated civilization spread around the Mediterranean, a trading and shipping conglomerate unmatched elsewhere.

This conglomerate received a very heavy blow to its existence when, around 1500 BC, the island of Santorini (Thera) exploded in a giant volcanic explosion, thought to have been four times the size of the 1883 explosion of Krakatoa in Indonesia. More details of these events may be found in CM604: Minoan Pants: A fashion item from a very unusual source [17].

A large part of the island of Santorini exploded up into the stratosphere, to fall as volcanic ash over a wide area. On Santorini itself, the resultant layer of ash was 40 metres deep, engulfing the town of Akrotiri.

Although the Phoenician site on Santorini was, of course, completely razed, the Explosion also led to tsunamis and immense waves of pyroclastic flows which devastated the coastal areas of much of the eastern Mediterranean. This Destruction Zone naturally included the majority of Phoenician cities, since they were all coastal-based.

It appears that, with typical prudence, the Akrotiri people may have been warned enough by the volcanic rumblings before the major explosion to have all left their city, since no skeletons have been found in Akrotiri. Unfortunately, many may been claimed by the widespread after-effects -- tsunamis being particularly fatal for their fleets of trading ships. So although the Knossos centre was eventually rebuilt, it never recovered its former heights.

There is but one God, and Her name is .....

A superb recent book by Nanno Marinatos, daughter of the archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos, describes excavations at Akrotiri [15]. (This book can be viewed online as a PDF). Her introduction is informative.

"The excavations at Akrotiri, Thera (Santorini) began with Spyridon Marinatos in 1967 and are still in progress under the direction of Professor Christos Doumas. They have gradually revealed an ancient town of significant wealth, the finds of which have exceeded every expectation: almost every season has yielded new surprises.

As the thousands of fragments of wall paintings gradually become restored (and this is an on-going process), a new picture book on Minoan life and religion is emerging giving new insights into every-day life, international relations, myths and rituals.

I have been studying the frescoes for many decades, but only recently did it become evident to me that Sir Arthur Evans' early view about the existence of monotheism in the Minoan age was essentially correct. Indeed, Akrotiri yielded evidence not of polytheism, but of one single female Great Goddess".

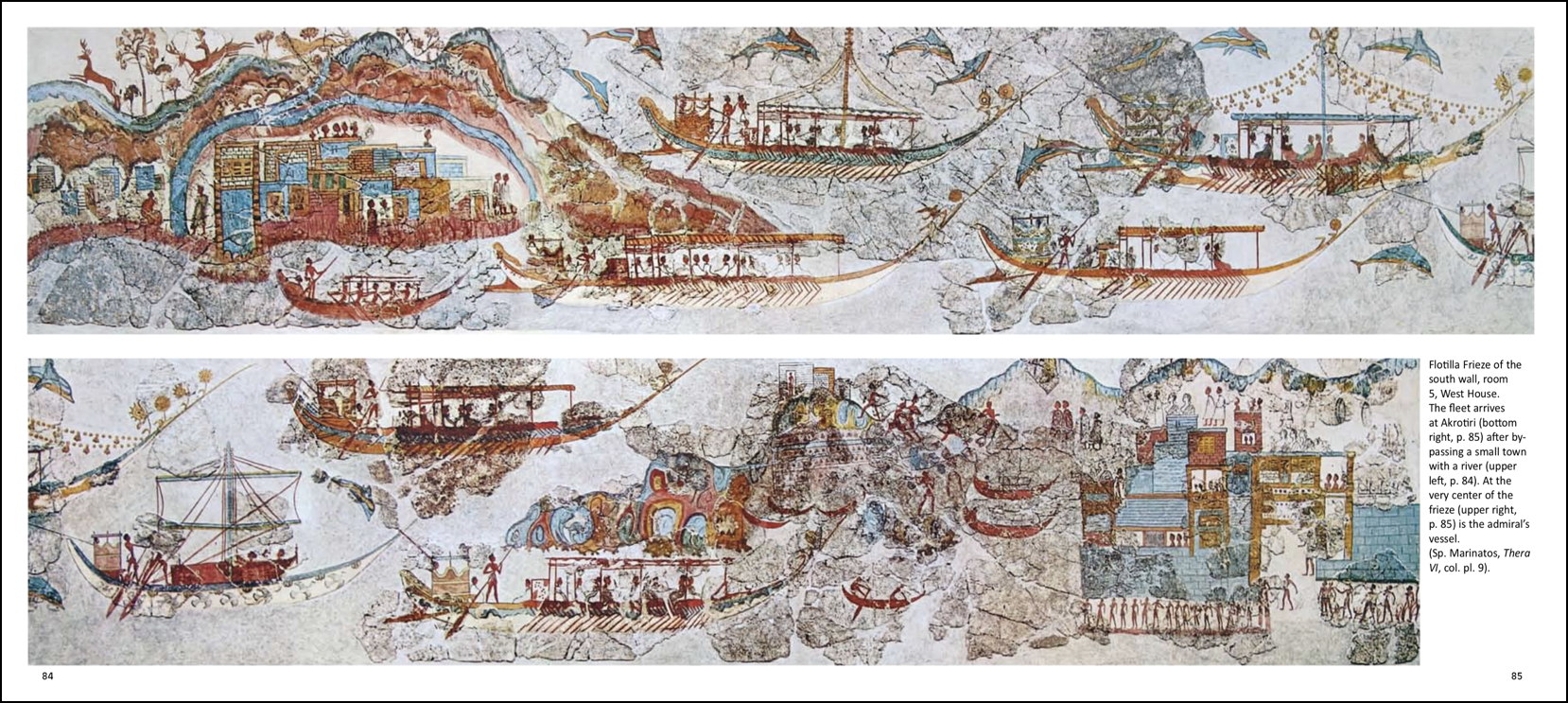

Figure CM608-F10. Frescoes from a house wall in Akrotiri, Thera. From [15].

Many of the buildings at Akrotiri were the private houses of individuals, rich sailor-traders in the Phoenician tradition. It was the custom at the time for house-owners to decorate their reception rooms with lavish wall-paintings, such as those shown in Figure F10.

The frescoes shown are from a three-storey house belonging to someone who had obviously become rich from sea trading, and prominently depict the ships used in this trade. An indication of the advanced social state of people then, is that the house (designated "The West House") contained an upper-floor toilet, connected by pipes to the town sewerage system.

This is in 1550 BC, more than a thousand years before Classical Greece or Rome! South of Crete was the ancient civilization of the similarly sophisticated Egyptians, who were valued associates (and good customers) of the Phoenicians. But even the Egyptians were not advanced enough to have individual sewered house toilets.

About Defending Yourself

Another point about the Knossos and Akrotiri sites, and virtually all other known Phoenician sites, is that they didn't have built defences. In most of the world, historical accounts are packed with stories involving castles, stockades, city walls, moats, and the like, and involving battering rams, catapults, and every sort of offensive weapon.

The Phoenicians did without these. They relied upon sites with natural defences, such as poor access. When their frescoes show weapons, these appear to be ornamental or used in rituals rather than conflicts.

Earlier it was mentioned how they tried to avoid fighting by befriending or buying off others. It could be said that instead of investing in Defensive Hardware, they went for Defensive Software -- a software solution is almost always better than a hardware solution.

When you look at how much modern nations spend on defence (the United States spent around 13.3% of its federal budget -- roughly $820 billion dollars -- on defence in 2023), you have to wonder whether this sort of money would been more effectively spent on "soft defence" rather than hard.

This would imply, as well as conventional foreign assistance, such things as sending in teams to build roads, bridges, hospitals, and tunnels, and especially, providing millions of full university scholarships, each potentially creating a life-long supporter.

In his book "Phoenician Secrets" [13], Sanford Holst recounts how the Phoenicians of around 1200 BC appeared to have successfully used this sort of soft defence. On the southern edges of the Black Sea, there existed the so-called Sea People, who due to various factors had suffered bouts of famine in the past, when the Phoenicians had helped them with supplies of food.

In 1182 BC there began a mass migration of the Sea Peoples towards the south, and hundreds of thousands of them swept down through what is now Syria and Lebanon towards Egypt, destroying and taking over every major city they encountered -- with the exception of all the Phoenician cities, which they left completely alone..

PART FIVE

The Antikythera Ship and its Contents

The superb source-book produced by Greece's National Archaeological Museum [3] gives a wonderfully detailed look at the matters concerned here.

Construction of the Ship

As to the ship itself, some pieces of its construction have been recovered, but the ship was very fragmented and so its reconstruction is somewhat tentative. According to [18], the ship was massive -- about 180 feet long (55 metres), with hull timbers 5 inches (13 centimetres) thick. That's as thick as those of ships built centuries later, during the American Revolution.

Figure CM608-F11. Details of the Antikythera ship planking. From [3].

The method of putting together the Antikythera ship's planking is highly sophisticated. The National Archaeological Museum book [3] notes "The ship's building technique. which used long planks edge-joined by mortise and tenons held in place with wooden pegs was considered unusual".

It also says :"Coagmenta punica, the Latin name for this type of construction, suggests a Punic origin."

Figure CM608-F12. The ship planking technique. From [3].

"Punic" is the Latin term for "Phoenician". So the shipbuilding experts are telling us that this was a Phoenician ship.

Contents of the Ship -- Cargo

The bulk of the Antikythera ship's cargo consisted of art objects, in particular marble and bronze statues and the like. Of these, some of the marble statues are particularly massive, such as four life-size horses, believed to be a team pulling a chariot (not recovered).

All the marble objects recovered have been identified as made of Parian marble, a fine-grained, semi translucent, and pure-white marble quarried during the classical era on the Greek island of Paros in the Aegean Sea.

Unfortunately, marble submerged in the sea is liable to attack by various marine organisms, and many of the statues salvaged were severely eaten away -- unless they happened to be partly or wholly covered by sand or silt. During salvage, some of the objects recovered were concealed beneath huge boulders, which were levered off and tipped into deeper water. These boulders turned out to be very severely eroded marble objects.

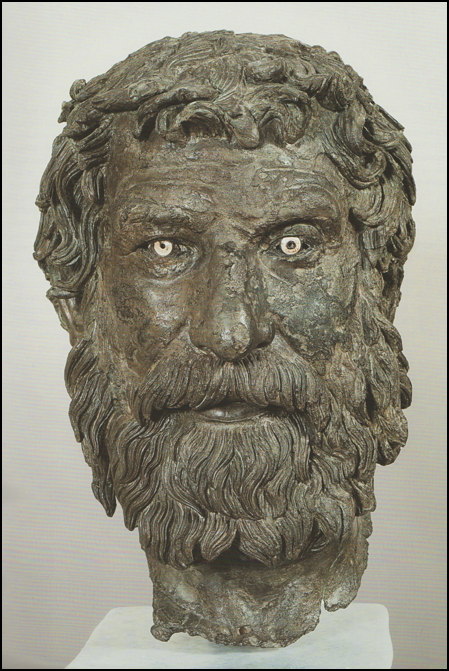

Bronze statues from the site were much better preserved. Although coated with limestone deposits, these could be carefully cleaned, revealing some spectacular figures.

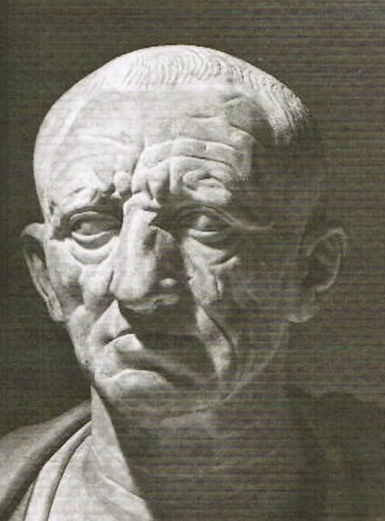

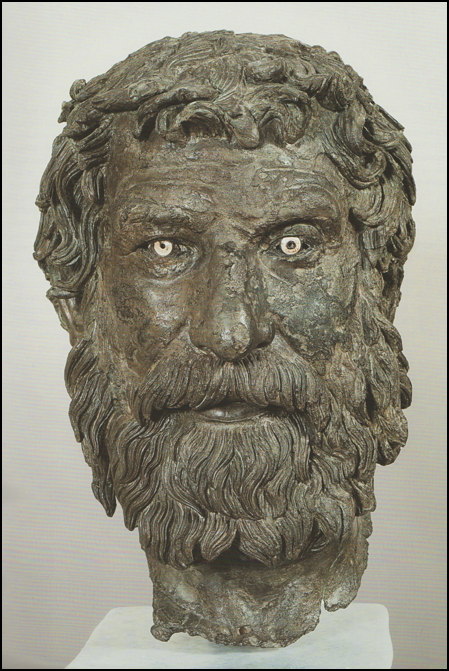

Figure CM608-F13. Bronze head of bearded man From [3].

Figure F13 shows one such bronze, the life-size head of a bearded man. It has been thought [3] to be the likeness of various Greek philosophers. It was made in the Middle Hellenic period, dated to around 220-210 BC. It might have originated in Rhodes.

With both marble and bronze figures, it seems generally accepted that their intended destinations were the villas of rich Romans, who liked to display Greek art as evidence of their interest in Culture.

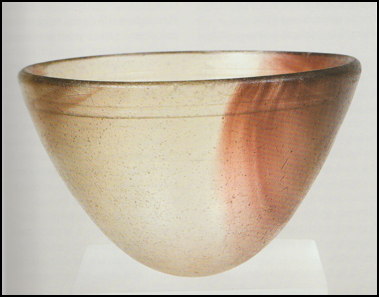

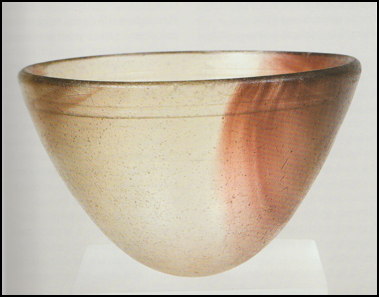

Another class of objects which have survived extremely well is those made of glass. Glass is not much subject to erosion, and if limestone or other deposits build up on them, these can be cleaned off relatively easily with chemicals.

Figure CM608-F14. Transparent glass bowl. From [3].

Figure F14 shows a very fine translucent glass bowl, which has survived two thousand years of sea immersion with no bad effects. The book [3] comments that it almost certainly originated from workshops along the Syro-Palestinian coast, which of course is the original Phoenician heartland.

The Phoenicians are acknowledged as the principal manufacturers of glassware in the Ancient World, including both utility and art objects. Some writers of the Roman period say that the Phoenicians invented glass. It might be slightly more accurate to say that they developed the first fine glasses which were colourless and transparent.

Figure CM608-F15. Multi-coloured glass bowl. From [3].

Figure F16 shows quite a different sort of glassware, called mosaic glass. Obviously an expensive art object, this bowl was probably made in Alexandria, Egypt [3].

Crew equipment and provisions

In addition, the ship's cargo contained a great deal of ceramic ware. Some of this was likely cargo items, intended for sale, while other items were containers, such as amphoras, which had held wine or olive oil -- items possibly for sale, or for use by the ship's crew while under way. Other items were clearly for crew use, such as cooking and drinking pots, and a few ceramic oil lamps. One item has the crew member's initials scratched on it.

Passenger items

The trading ships of the Phoenicians. and those of other nations, are known to have carried passengers. One of the finest Antikythera items was a pair of women's earrings (Figure F17). These were made from gold and adorned with pearls, garnets, and emeralds.

Figure CM608-F17. Gold earrings with Eros pendant. From [3].

Skeletal remains of at least four people were found at the wreck site, with at least one of them from a woman. So it seems very likely that the ship carried at least one well-to-do female passenger, who probably went down with the ship.

The War Dolphin

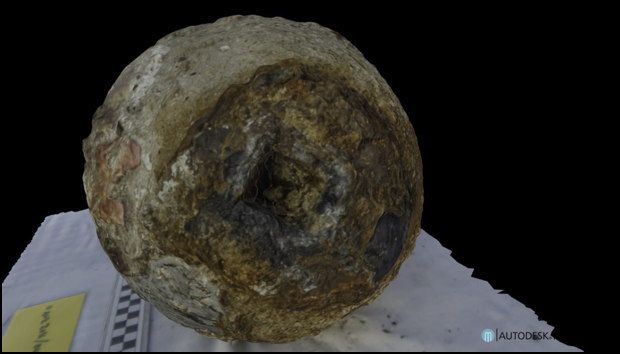

A unique item recovered from the Antikythera wreck was a torpedo-shaped cylinder noted as "unbelievably heavy". The cylinder was made of lead, and had a hole through it. No one knew what it was. To find clues, researcher Brendan Foley went back to ancient literature -- writings by the Greek historian Thucydides [20].

Thucydides wrote how the biggest ships in antiquity had these defensive armaments known as dolphins. When an enemy ship pulled alongside to board, sailors would hoist the dolphin up to their own yardarm, and then drop it on the enemy ship to put a hole in its hull.

Figure CM608-F18. The torpedo-shaped lead cylinder recovered from the Antikythera shipwreck. From [20].

Until the Antikythera discovery, no one in modern times had seen a war dolphin. It gave the Phoenicians a very effective defence -- a secret weapon -- against the pirate bands which plagued the Mediterranean at that time.

The Ship was Phoenician

Looking at all the details of the Antikythera ship, and what it carried, there can be little doubt that it was Phoenician. This was specialist trading to a high degree -- modern DHL and Sotheby's combined. Really, the only other contenders would have been the Romans, and they just didn't have the technology to build such a giant ship, nor were they particularly interested in having a trading fleet -- better leave that sort of vulgar work to the Phoenicians who swarmed in every port.

Sure, the ship was bound for a Roman port, and may even have been loaded to fill a Roman order, but was too specialist to be a Roman vessel. According to [19], early Romans were primarily a land-based power. Their main interest in ships was for war, not trading.

Their initial forays into naval warfare weren't very successful. During the Punic Wars (264-146 BC) against Carthage (a Phoenician colony), the Romans were at a disadvantage at sea. They realized the superiority of Carthaginian (Punic) warships.

According to the historian Polybius, the Romans got a lucky break in 264 BC. A beached Carthaginian warship provided them with a first-hand example of Phoenician shipbuilding, including a key technique called Phoenician joints.

The Romans quickly grasped the advantages of the design. Phoenician joints allowed them to use less-dried timber, speeding up construction. This helped them build a large fleet (100 quinqueremes) in just two months! [19].

They were helped in this by the Phoenician technique of labelling each part in a ship build, like an IKEA flatpack, so parts could be reproduced in large numbers and assembled in a "production line". Rome replicated that Carthaginian vessel over a thousand times in rapid order (within 1 to 2 years) and put them to sea, several hundred at a time. It turned the tide of the 1st Punic War in Rome's favour.

The Antikythera Mechanism as a Phoenician GPS

Most recent researchers have taken it as a given, that the Mechanism was principally a predictive show device -- turn the handle, slot in the gears, and it will show you the phase of the moon, when the next eclipse will appear, or where the planets will be in the sky.

The concept of it being an impressive showpiece to wow an audience, and gain prestige and fame through its possession, just doesn't hold water. Both the Romans and the Greeks were good at publicity, writing about the marvels they held and the feats that they had accomplished. Where have they claimed such a marvel as the Antikythera Mechanism?

Also, the Mechanism showed signs of having been repaired. This is what we might expect from a working instrument, not from a showpiece.

Turn the concept on its head. Assume a ship's navigator or skipper feeds all his observational data into the Mechanism, and in so doing, it gives him the ship's exact position at sea -- how valuable is that? And in a competitive world, who would you let know about it?

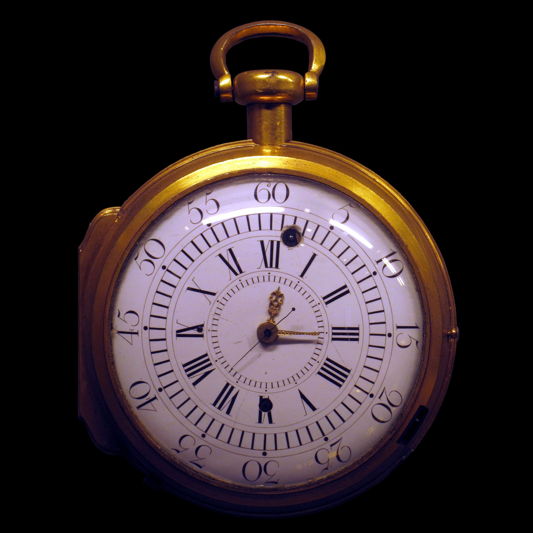

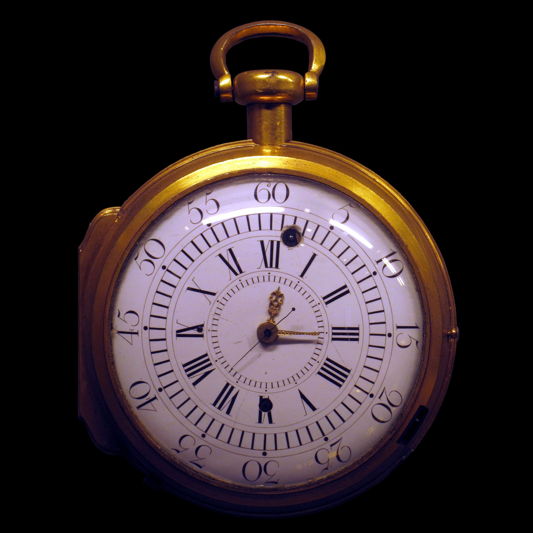

At sea, it's not difficult to find your Latitude (your position relative to the poles and the equator), but Longitude is a different matter. Finding your Longitude was a task not resolved in modern times until the development of the Marine Chronometer, in the 1700s. Knowing the time difference between where you were (findable from instruments) and where the chronometer had been set (usually the meridian of Greenwich, near London) gave you your distance from this meridian.

The Marine Chronometer

Wikipedia gives us the story [21] of how the marine chronometer was developed in England.

"A marine chronometer is a precision timepiece that is carried on a ship and employed in the determination of the ship's position by celestial navigation. It is used to determine longitude by comparing Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), and the time at the current location found from observations of celestial bodies.

When first developed in the 18th century, it was a major technical achievement, as accurate knowledge of the time over a long sea voyage was vital for effective navigation, lacking electronic or communications aids. The first true chronometer was the life work of one man, John Harrison, spanning 31 years of persistent experimentation and testing that revolutionized naval (and later aerial) navigation".

Producing a completely satisfactory timepiece which would function in an environment of stormy seas and heat extremes was by no means simple. But there was a carrot offered to those willing to put in the effort.

"In 1714, the British government offered a longitude prize for a method of determining longitude at sea, with the awards ranging from £10,000 to £20,000 (£2 to £4 million in 2024 terms) depending on accuracy [21]. John Harrison, a Yorkshire carpenter, submitted a project in 1730, and in 1735 completed a clock based on a pair of counter-oscillating weighted beams connected by springs whose motion was not influenced by gravity or the motion of a ship.

His first two sea clocks had a fundamental sensitivity to centrifugal force, which meant that they could never be accurate enough at sea. A third machine, in 1759. included novel circular balances and the invention of the bi-metallic strip and caged roller bearings, inventions which are still widely used. These still proved too inaccurate, and he eventually abandoned the large machines.

Figure CM608-F19. Ferdinand Berthoud's marine chronometer no.3, 1763. From [21].

Harrison finally solved the precision problems in 1761, with a much smaller chronometer design which looked like a large pocket watch. His design used a fast-beating balance wheel controlled by a temperature-compensated spiral spring. These features remained in use until modern times, when stable electronic oscillators were developed.

Harrison submitted his 1761 design (coincidentally, almost exactly the same size as the Antikythera Mechanism) for the £20,000 longitude prize, which he was eventually awarded, but only after a long tussle with Nevil Maskelyne, the then Astronomer Royal, who had taken a dislike to him.

PART FIVE

The World at the Time of the Antikythera Wreck

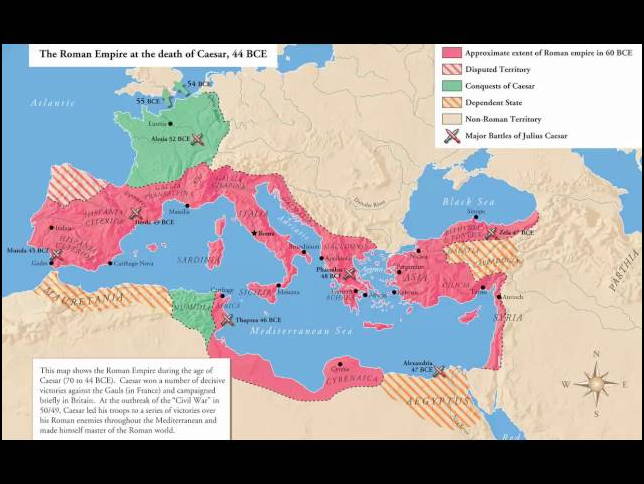

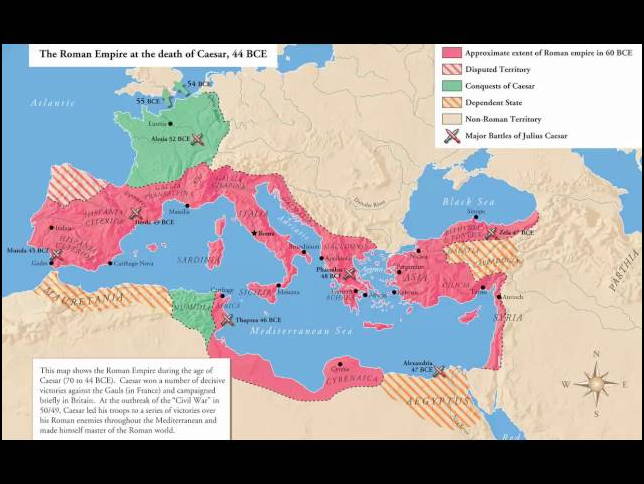

The last 400 or so years of the BC period were ones in which the predominance and power of the various political groups underwent huge shifts. In 400 BC, Rome was a small localized power in Central Italy, while Greek and Phoenician cities populated most of the Mediterranean lands, living in generally peaceful cooperation.

Figure CM608-F20. The Mediterranean World in 550 BC. From [24].

Figure F20 shows a map of the Mediterranean region around 550 BC. It can be seen that the Greeks occupied parts of the east coast of what is now Spain, the coast of France, most of the Black Sea coast, Cyprus, the Libyan coast, part of Sicily and Corsica, and the southern third of Italy, as well as modern Greece.

The Phoenicians occupied most of the northern African coast, quite a lot of coastal Spain, the Balearic Islands, parts of Sardinia and of Sicily, as well as their original homelands in Lebanon.

At that time, Rome was just a small town in central Italy. In 435 BC it commenced its expansion, gradually taking over or conquering all the rest of the Italian peninsular, and taking Corsica, Sardinia, and Sicily from the Greeks and the Phoenicians (Figure F21).

Figure CM608-F21. Roman territory, 500-218 BC. From [23].

Most of this expansion was by varying degrees of force. Areas resisting Roman rule could look forward being looted, with their people killed or sold into slavery, then existence as a tribute territory, required to send taxes and supply food and merchandise to Rome, the capital. Men were conscripted into the Roman army, usually serving in remote areas of the empire, with the chance to obtain Roman citizenship after 25 years.

Figure CM608-F22. Roman territory in 44 BC. From [22].

With its vast and mobile conscript army, Rome was able to concentrate troops at its latest aggression point and smash any opposition in most of its battles. But one city took a great deal of effort to overcome, the Phoenician city of Carthage, on the north African coast in what is now Tunisia.

In Phoenician society, women usually held as good a status as men, and its history records many strong women. Carthage was founded by a Phoenician colonization party led by Queen Dido in around 814 BC. Over the centuries it became outstandingly prosperous and sophisticated, the third great focus city of the Phoenicians, after Knossos and Tyre. Carthage had luxurious six-storey buildings and was the epitome of a great metropolis.

So Carthage had considerable resources, and in its inevitable clash with Rome, it took the Romans almost 120 years, and three wars, to finally overcome them. These wars are known as the Punic wars. and ran between 264 BC and 146 BC.

There are plenty of good accounts of the Punic Wars, so we won't go into them in detail here. Briefly, the First Punic War was fought over Rome taking over the island of Sicily, just off the southwest coast of the Italian mainland. It was during this war that the Romans learnt how to make many copies of a Phoenician ship, as already mentioned. That war ended with the Carthaginians giving up their Sicilian sites and agreeing to pay Rome a big sum of money.

In the Second Punic War, Rome attacked the city of Carthage (in contravention of an agreed treaty) and was eventually bought off with another onerous financial settlement. Carthage had no conscript army, and usually handled armed conflicts with mercenaries or by negotiation, but did have a military command group, headed by Hamilcar Barca.

Hamilcar Barca was a Carthaginian general and statesman, and father of the famous Hannibal. Hamilcar commanded the Carthaginian land forces in Sicily from 247 BC to 241 BC, during the latter stages of the First Punic War. The Carthaginians were pretty annoyed with the Romans by this time, and Hamilcar was all for mounting a major attack on Rome.

The Carthaginian City Fathers were not especially keen on this, so Hamilcar took matters into his own hands. He shifted his operations, with his son Hannibal (who at an early age was made to swear eternal hostility to Rome), to Spain, where he set up silver mining and trading enterprises. With typical Phoenician know-how, he soon accumulated funds for a major campaign, and this was the start of Hannibal's famous trek with soldiers and war elephants, up through France and the Alps to northern Italy.

Hannibal fought and won many battles against the Romans in Italy, at one stage reaching the gates of Rome. But illness and limited resources stopped him from taking the city. Eventually he was drawn off by the Romans sending ships against Carthage, leading to another ignominious settlement.

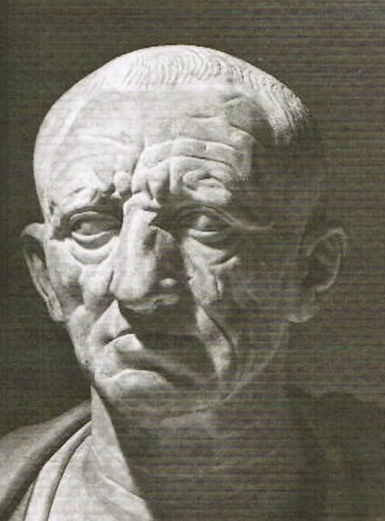

Meanwhile, in Rome, Carthage had generated a fearsome opponent. Marcus Porcius Cato, better known as Cato the Elder (234-149 BC), was an influential political figure of the Roman Republic [25]. Serving as quaestor, aedile, praetor, consul, and censor, he championed Roman virtues and detested Greek culture. He wrote the first Roman histories in Latin and was an eloquent orator. Towards the end of his career, he advocated for the Third Punic War with his famous line, "Carthage must be destroyed."

Figure CM608-F23. Cato the Elder. From [25].

Egged on by Cato, the Roman army, commanded by General Scipio Aemilianus, besieged Carthage and eventually seized it in 146 BC. After this capture, a large part of the population was massacred, and the survivors were enslaved, as was customary in ancient times. The Romans then spent the next year tearing down every structure in Carthage, right to the ground.

PART SIX

The Four Questions

Here are the four Questions asked previously. We are now in a position to add detailed Answers.

Question One. Who made the device?

Question Two. What was it used for?

Question Three. Why was it not mentioned in writings of the time?

Question Four. Why was it never developed further?

The Answer to Question One, "Who made the device?" is clearly, The Phoenicians. It is very understandable that the common answer to this question has been "The Greeks", with its finding location, its discoverers, and much of the effort and funds put into its investigation over the last century being Greek (modern). Also, the makers of much of its cargo of statues were Greek (classical).

In addition, the language of the thousands of characters inscribed on the device was Greek. But it has to be understood that this was "Koine Greek" or common Greek, which was the international language of the Mediterranean world in Antikythera times, just as English is the international language today.

Every country which has an international airline today will have an English-speaking crew and passenger signs in English (as well as signs in its own language and script). In the same way, every Phoenician trading ship of the late BC world would have had a Koine-Greek speaking crew.

Evidence has been given above that, in fact, the ship and its crew were Phoenician -- they are the only likely contenders, when giving due consideration to economic motives and general capabilities.

The Answer to Question Two, "What was it used for?" is here claimed to be that it was A GPS Device, that is, a navigational tool used by the crew to determine their position in the world.

The complexity of the Antikythera Mechanism is such, that it must have been the result of decades, even generations, of continued effort and skill -- it could not have been a one-off, but instead, was Model X in a long range. This sort of investment almost certainly reflects something giving a long-term commercial advantage for its owners.

As for the detailed scientific knowledge of the heavens needed to construct such a device, that almost certainly did come from the Greeks. The main source was probably Hipparchus, considered the greatest ancient astronomical observer and, by some, the greatest overall astronomer of antiquity.

Wikipedia tells us [26] "Hipparchus (ca 190 -- 120 BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his discovery of the precession of the equinoxes.

Hipparchus was born in Nicaea, Bithynia, and probably died on the island of Rhodes, Greece. He is known to have been a working astronomer between 162 and 127 BC.

Hipparchus is considered the greatest ancient astronomical observer and, by some, the greatest overall astronomer of antiquity. He was the first whose quantitative and accurate models for the motion of the Sun and Moon survive. For this he certainly made use of the observations and perhaps the mathematical techniques accumulated over centuries by the Babylonians and by Meton of Athens (fifth century BC), Timocharis, Aristyllus, Aristarchus of Samos, and Eratosthenes, among others.

He developed trigonometry and constructed trigonometric tables, and he solved several problems of spherical trigonometry. With his solar and lunar theories and his trigonometry, he may have been the first to develop a reliable method to predict solar eclipses.

His other reputed achievements include the discovery and measurement of Earth's precession, the compilation of the first known comprehensive star catalog from the western world, and possibly the invention of the astrolabe, as well as of the armillary sphere that he may have used in creating the star catalogue."

The astrolabe and the armillary sphere were mechanical devices for displaying the movement of heavenly bodies, and so are natural predecessors of the Antikythera Mechanism. What distinguishes the latter is its use of gears, many of them, in developing a professional working tool from display pieces used to impress and educate.

The Answer to Question Three, Why was it not mentioned in writings of the time? is because, as shown above, the Phoenicians had a policy of keeping their best technical advances close to their chests. Retaining the secrets of running a trading enterprise, while active in selling its products to all, is commonsense in a competitive commercial world.

The Answer to Question Four, Why was it never developed further?

is because of the gradual suppression of the Phoenicians as a somewhat distinct ethnic group. Figure F22 above shows how, by 44 BC, the Romans were in control of virtually every area of the Mediterranean which contained a Phoenician city.

The Phoenicians never viewed themselves as a closed society, and made no attempt to restrict "marrying outside" their own social groups. In fact Phoenicians were known for intermixing with other cultures. They established trading colonies around the Mediterranean, leading to a blending of ethnicities.

Because of the Phoenician use of a "Company Secret" approach to technology, knowledge of the Antikythera Mechanism would have been restricted to a "closed shop" of navigators and captains in their fleets. When all commercial activities were under the thumb of the Romans, these types of independent traders would have tended to disappear.

Some researchers have attempted to put a date to the end of the Phoenicians as a segment of society, for example 42 BC or 44 BC. If this figure is correct, it would mean that the Antikythera ship would have been one of the very last trading ships that they operated.

We can talk about Phoenician Genes and Phoenician Memes. Being an open group of diverse origins, locations, and circumstances, it's likely that any distinctive genes that they possessed would have merged into the general gene pool -- we probably all have some of these genes. Some famous people, for example the classical Greek mathematicians Pythagoras and Euclid, are known to have had a Phoenician parent.

As for Phoenician Memes -- in the original sense of self-propagating ideas or knowledge nuclei -- these would have tended to fade when their social groupings died out. But there are two areas where some persistence can be guessed at.

The first is the Arab World. Just as the story of the Phoenicians is not well known, so also is general appreciation of the prominence of the Arabs during the "Dark Ages" of Europe, from around 500 AD to 1400 AD. During this period, the Arabs carried the banners of science and culture -- with their metropolis in Timbuktu, now thought of as an African backwater.

Many thousands of books and manuscripts in Arabic are known to exist in collections held in the countries of the broader Saharan area, with the vast majority never subjected to modern scrutiny and translation. These collections may hold Arabic versions of many "lost" Greek and Latin classics, as well as the works of Muslim scientists and scholars of the day.

It is very possible that some of the specialist knowledge of the Phoenicians, particularly those in their last great metropolis of Carthage, on the north African coast, may have moved down to the burgeoning civilizations to their south. This would explain the appearance of geared water clocks around 1000 AD in this area.

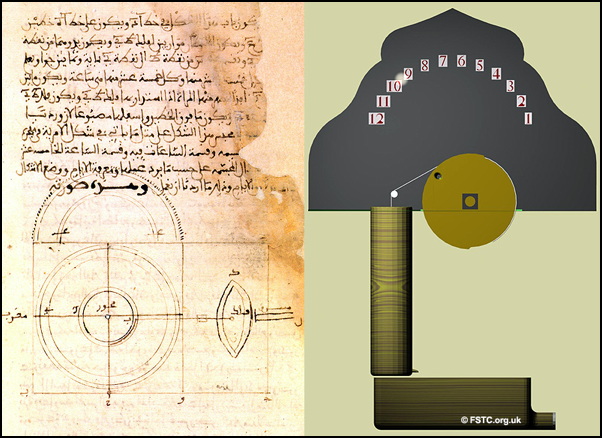

Arab Water Clocks, 1000 AD on

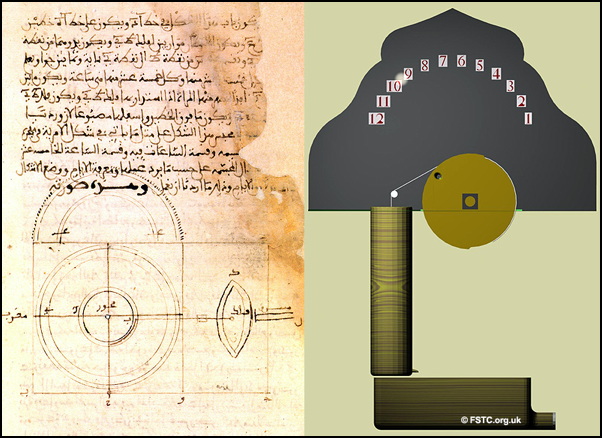

Some of the earliest descriptions in Arabic of water clocks are available in Al-Muradi's 'The Book of Secrets' [27]. The treatise describes 31 models, of which five are essentially very large toys similar to clocks, in that automata are caused to move at intervals, but without precise timing.

Figure CM608-F24. Al-Muradi describing the solar clock in his "Book of Secrets" (on the left), 3D computer animated image of solar clock (on the right). From [27].

In the book there are nineteen clocks, all of which record the passage of the temporal hours by the movements of automata. The power came from flowing water, and it was transmitted to automata by very sophisticated mechanisms, which included gears and the use of mercury. These are highly significant features; they provide the first known examples of complex gearing used to transmit high torque, while the adoption of mercury reappears in European clocks from the thirteenth century onwards.

These Arab clocks were clearly the forerunners of the Medieval clocks of Europe, such as the famous Prague Astronomical Clock, dating back to 1410. The fact that this clock is loaded with astronomical features shows its affinity with the Antikythera Mechanism.

Figure CM608-F25. The Prague astronomical clock). From [28].

The Prague astronomical clock is a medieval astronomical clock attached to the Old Town Hall in Prague, the capital of the Czech Republic. The clock was first installed in 1410, making it the third-oldest astronomical clock in the world and the oldest clock still in operation [28].

The clock mechanism has three main components -- the Astronomical Dial, representing the position of the Sun and Moon in the sky and displaying various astronomical details; statues of various Catholic saints stand on either side of the clock; The "Walk of the Apostles", an hourly show of moving Apostle figures and other sculptures, notably a figure of a skeleton that represents Death, striking the time; and a Calendar Dial with medallions representing the months.

The other likely descendant of the Antikythera Mechanism is the "sundial calendar" mentioned back in Part Two. In 1983, this item was offered on sale to Michael Wright and Jennifer Field, of London's Science Museum, by a Lebanese collector who said that he had bought it from a street trader in Beirut [7].

You will remember that Wright and Field were actively trying to work out how the Antikythera Mechanism worked at that time. They managed to find the funds to buy the device from the collector. It contained only four gears, and from Greek inscriptions mentioning places in Byzantine times, such as Constantinople, was tentatively dated to around 500 AD [7].

The intriguing point here is that the sundial device was said to have been found near Beirut, in Lebanon. This is precisely the place where, in Part Four, the Phoenicians were noted as having originated.

Other Phoenician Memes

The best-known memes or concept ideas which have come down to us from the Phoenicians are the invention of the Alphabet (a script where symbols represent specific sounds), and the development of ship-building techniques, including invention of the keel.

According to the present article, a further nautical meme which should be attributed to the Phoenicians is the invention of a navigational tool. Of course, the Phoenicians are already acknowledged as master navigators, but underlying reasons for their skill have not previously been recognized.

Another of their memes which is probably poorly recognized is their development of good-quality clear glass. The importance of this in modern civilization is seldom pointed out, but it was at the heart of the many modern scientific developments beginning in late 1600s Europe, as exemplified by Isaac Newton's book "Opticks", published in 1704. Lenses and other optical components are only possible with the availability of high-quality glass.

This scientific revolution was initially unique to Europe, owing little to other parts of the world. For example, it has been suggested [29] that China, home of many great inventions, missed out on this revolution because their mastery of (opaque) ceramics blinded them to the virtues of glass, which they relegated to the areas of toys and display art objects.

But perhaps their greatest meme is the one in the operation of civilizations, the idea that a peaceful, long-living, and prosperous society can be attained through unsolicited gifts and aid to sister groups who are your neighbours.

On the whole Antikythera topic, there are some good video treatments available for streaming, such as [30].

PART SEVEN

Western Australia

If Antikythera-type navigational tools were used by the Phoenicians in the late BC centuries, it might be expected that other examples of them might be found in other Phoenician shipwrecks of that era.

Although the Antikythera Mechanism is quite complex, it would not have been particularly hard to produce multiple copies quite quickly, enough for all the larger ships of a fleet. With a complete loose set of all the parts involved, these could be laid out on a bronze sheet and inked around the edges, with the marked sheet given to an apprentice to cut and file out.

The more skilled workers of the workshop could then add the final touches and assemble and check the final device -- maybe only a matter of a day or so. We have already seen that the Phoenicians were familiar with mass production, in their shipbuilding.

So it would be reasonable to expect these navigational devices to be used in all Phoenician ships of that era, say around 250 BC to 50 BC. There may be many Phoenician wreck sites worth investigating here. Recent advances in remote undersea exploration devices make formerly difficult-to-access wrecks a possibility for such searches.

Sites used by the Phoenicians have been claimed in many parts of the world distant from the Mediterranean. Some are well established, as with the tin mines of Cornwall in the southwest of the UK, and on the West African coast, possibly as far south as Senegal. But there are two claimed Phoenician sites as far away as Australia.

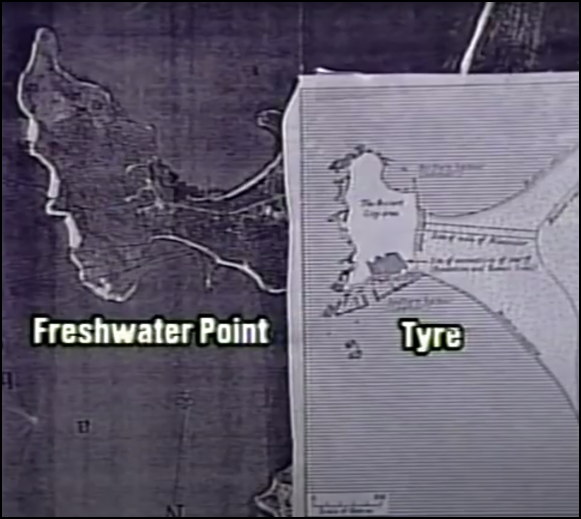

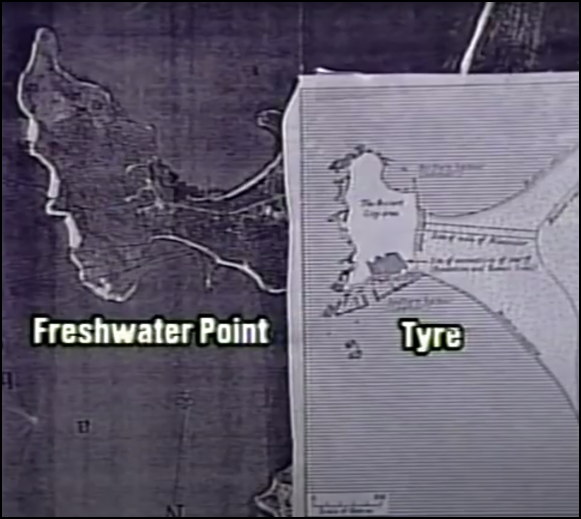

The first of these is at a locality called Freshwater Point, in the former shire of Sarina, near Mackay on the coast of Queensland. Here is some of what [31] says about the Sarina site.

"The Freshwater Point site is one of many around Australia's coastlines and it is almost an exact copy of Tyre of Phoenician legend. The east harbour jetty is a typical Phoenician loading platform of granite stone set in furnace-slag cement, some 400 metres in length by 30 metres width by 5 metres high, running back to a freshwater spring and reservoir. "

Figure CM608-F25. Similarity of the Phoenician sites at Tyre, Lebanon, and Sarina, Queensland. From [34].

"This reservoir is one of two on the isthmus relative to adjacent open cut mines accessing gold, copper, metacinnabar, epidote, arfedsonite, etc with associated slag heaps and artifacts with the usual Bel altars on the skyline. In conjunction with this east harbour, Sarina inlet contains walls, a cemetery, a Tanit shrine, a boatyard with launching ramp, giant ten-acre fish traps and the usual petroglyphs.

Sarina's harbours dictate a Phoenician engineering and are associated with other harbours in the giant Broadsound archipelago, where the engineers gave top priority to their precious ships prior to establishing operations. Aerial photographs clearly show eroded harbours and walls, reservoirs, etc relative to nearby surface and alluvial mining with quarry chip roads a very pertinent feature. "

In 2003, Grant McAuliffe prepared a 25-minute video on Sarina, "Phoenicians In Australia 3,000 years ago", now available on YouTube [34]. It's inconceivable that the images in this video are fake, yet official powers appear to take the view that the site does not exist.

In [31] it notes "Research to date has been limited to surface visuals by private researchers, with a refusal of academia to participate on political grounds. Officially, the sites do not exist. Current controversy relative to Aboriginal land claims has the Government somewhat paranoid about a possible land claim by outsiders, relative to the overwhelming evidence being uncovered of such colonies in the BC era. Academia is strictly limited in its research to Aboriginal cultures."

Western Australia

The second claimed Phoenician site is in the Buccaneer Archipelago, on the north coast of Western Australia, my home state. This region is named after the English buccaneer William Dampier, who visited Western Australia on two separate occasions. His first visit was in January 1688 as part of a privateering voyage on the ship Cygnet. They landed near King Sound (close to present-day Broome) for repairs and stayed for two months. His second visit was in August 1699.

Buccaneers were essentially pirates, but were actually often licensed by their governments to take over the ships of other nations, as a normal commercial operation. Dampier himself was an outstanding observer, natural scientist, chart-maker, and writer, with his work influencing later famous people, including Captain James Cook, Horatio Nelson, Charles Darwin, Jonathon Swift, and Alfred Russel Wallace [37].

Dampier was born in Cornwall, the source of some of the tin metal traded to the Phoenicians in BC times. So it is not impossible that he may have carried some Phoenician DNA.

Figure CM608-F26. The Buccaneer Archipelago, northern Western Australia. From Google Earth.

The original claim of a Phoenician site is essentially based upon a book published in 1980 by a well-known West Australian diver and treasure hunter called Alan Robinson.

Robinson was a controversial figure, always in conflict with the authorities on various grounds. Today, many consider he was victimized because of his stubborn stands -- he mounted two High Court cases against the WA State Government, and won both of them, which must have grated. There is evidence that he was beaten up by the police of those times.

Robinson's book recounts many of his experiences, and reads very credibly. In Chapter Nine of the book, he tells of being approached in Derby (a town on WA's northern coast) by an old prospector, known as Shallow-Well Charlie. This would have been in the early 1970s.

Figure CM608-F27. Cover of Alan Robinson book "Treasure in Australia" .

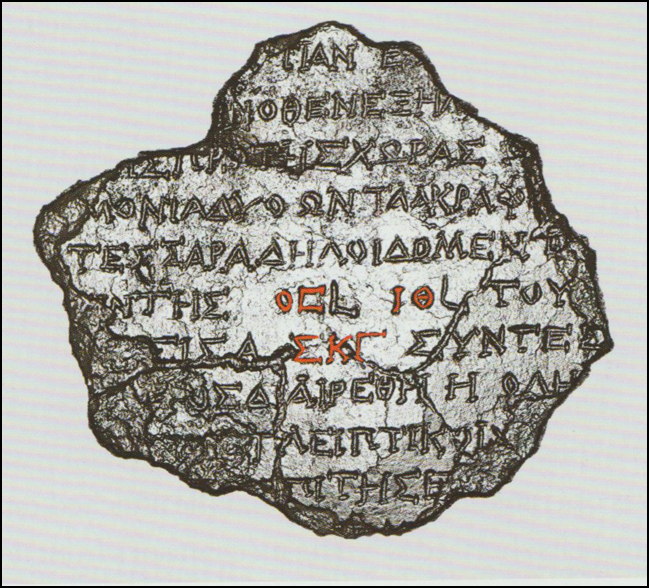

Charlie knew of Robinson's experience with items salvaged from sunken ships, and asked if he could help identify an inscribed bronze tablet he had found in the shore mud of a site in the Buccaneer Archipelago, adjacent to what he said was a long-abandoned mine, a source of Galena (a lead ore, usually also containing silver and other metals), and a possible shipwreck just offshore, with part visible above water only at low tide .

(For convenience of consultation, a transcript of the whole of Chapter Nine has been made, and put up on the Web at Chapter Nine, as a PDF [36].)

Naturally, Alan Robinson was intrigued by this revelation, and wanted to see the site of the mine and possible wreck. However, overland it would be a 200-kilometre donkey trek through the scrub from the nearest road, and sea access was difficult because of the huge (11 metre) tide and the thick mud and mangroves.

So Robinson arranged to hire an aircraft the next day, and have the pilot fly it out to the spot Charlie indicated and arrive there just before low tide. Robinson describes how he had loaded two cameras with new film and used them on their approach to the site and on snapping a banana-shaped object in the mud -- one he thought was more like a canoe in shape than a typical sea-going craft.

At Alan's request, the pilot had held the plane at an altitude of 500 feet at the site, so the sizes of objects on the two rolls of film used could be worked out.

With the existence of the mine and possible shipwreck confirmed, attention turned to the inscribed bronze tablet found in the shore mud. The inscription was in a script unknown to both of them -- Charlie wondered if it was Chinese, but Alan knew it was not.

So Alan sent the tablet to be identified at an organization in the United States, and started on a Channel Seven television project, filming sharks at two areas on the West Australian coast. What followed is described in a verbatim quote [36] from Chapter Nine of Robinson's book.

I returned home for a well earned rest, but three days later a registered parcel arrived addressed to me from the United States.

Opening it, I removed Charlie's bronze tablet and then hastened to read the accompanying letter. Quote.

"Dear Sir,

"We wish to thank you for the opportunity to identify the enclosed bronze plate, which we found to be extremely interesting.

"It is of Phoenician origin possibly from a period 200 -- 700 B.C.

"At present, we are not able to translate fully, the text of the writing on the plate. This is being investigated by Professor Mason of our archeological section, who will forward his findings at a later date.

"We would appreciate any further information you could send regarding location of your discovery as we consider it of important historical significance." Unquote.

Alan immediately wrote to Charlie with the news, and wanting to make it public, he approached the then Director of the West Australian Museum, Dr W D L Ride, with news of the discovery. He was fobbed off by Dr Ride. It should be explained that at the time, Alan and Dr Ride were at arm's length because Alan was disgusted with the Museum's treatment of other salvage he had given them -- five priceless pots had been smashed to pieces -- and because of disputes over the ownership of salvaged coins.

Alan also investigated Phoenician voyages of exploration, and how they built their ships, with books in the State Library in Perth. He found references to their trips to places as far away as China. He also notes "Another book gave details of the structure of a Phoenician Trireme as 165 ft long and only 20 ft wide (just like a banana)."

Three years after the publication of his book [35], in 1983, Alan Robinson died in somewhat mysterious circumstances while being held on remand in Sydney's Long Bay Gaol. At the current time (2024) we are left with a number of unanswered questions.

Question A. Where is the inscribed bronze tablet now, if it still exists? Is it another example of a Phoenician navigation device, like the Antikythera Mechanism?

As to the tablet's provenance, there can be little doubt that it was Phoenician. It was identified as such, without prior suggestion, by the American institution to which it was sent for appraisal. This can only be because the inscriptions on it were in the distinctive Phoenician alphabet.

Question B. What was the American institution which did the assessment of the tablet?

So far, nothing more has become apparent as to the identity of this institution. From the reference to "Professor Mason of our archeological section", it could well be a university, but another type of research or history centre is also a possibility.

Question C. Do copies of relevant photographs taken by Alan Robinson still exist, and if so, where? Almost certainly the American institution which investigated the tablet would have taken photographs, where are these?

Question D.

Does the mine site and ship wreck described in Robinson's book really exist, and if so, what is its exact location? (for convenience of identity, the ship is being referred to as the "Buccaneer Phoenix").

Current (2024) work

I and colleagues in the Buccaneer Historic Precinct Association Inc [38] have made some pleasing progress with answering Question D, with only limited results with answering Questions A to C.

Using published maps and guides, Alan Robinson's description of his visit, Google Earth, and satellite imagery services, we believe that we have located the site of the mine and of the "Buccaneer Phoenix" in the Buccaneer Archipelago.

And we believe that we may have found the ship. Figure 28 shows an enlargement of a satellite image of the identified site, showing an underwater object which could be the ship.

Figure CM608-F28. Shadow of the Phoenician ship "Buccaneer Phoenix"? .

The resemblance of this object to the banana shape noted by Robinson is apparent. Moreover, the object is estimated at about 30 metres long, which would be right for a Phoenician ship.

A current aim of BHPAI is to find financial and other support for a helicopter expedition to the site, to confirm or deny the existence of the ship and the mine.

BHPAI would also welcome information and suggestions on locating the photographs by Alan Robinson or the American institution about the site or the bronze tablet, or even discovering the tablet itself. Today's staff of the West Australian Museum have kindly conducted a search of their stock records, but have been unable to locate this tablet.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

References and Links

[1]. Derek De Solla Price. Gears From The Greeks. The Antikythera Mechanism -- A Calendar Computer From ca 80 BC. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 64, part 7,1974.

[2]. James Pasley. Vintage photos show how deep sea diving and exploration has evolved over the years. https://www.businessinsider.com/vintage-photos-show-evolution-deep-sea-diving-2023-6 .

[3]. The Antikythera Shipwreck: the ship, the treasures, the mechanism. Athens, National Archaeological Museum. 2012.

[4]. Ed Mazza. 2,000-Year-Old Antikythera Shipwreck Famous For 'Ancient Computer' Yields New Treasures. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/antikythera-shipwreck_n_5768b582e4b015db1bca7547.

[5]. Alexander Jones. A Portable Cosmos. Revealing the Antikythera Mechanism, Scientific Wonder pf the Ancient World. Oxford University Press, 2017. ISBN: 9780190931490.

[6]. Andrew Prestridge. 5000 Years of Gears - Timeline. https://evolventdesign.com/blogs/history/5000-years-of-gears .

[7]. Jo Marchant. Decoding the Heavens. Solving the mystery of the world's first computer. Heinemann, 2008. ISBN: 9780434018352.

[8]. Tony Freeth et al. A Model of the Cosmos in the ancient Greek Antikythera Mechanism. Nature Scientific Reports, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84310-w .

[9]. Leonard Kelley. How Did the Antikythera Mechanism Impact Ancient Astronomy?. [Updated 2023]. https://owlcation.com/humanities/What-is-the-Antikythera-Device-and-How-Did-It-Impact-Ancient-Astronomy .

[10]. Tony Freeth. Eclipse Prediction on the Ancient Greek Astronomical Calculating Machine Known as the Antikythera Mechanism. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264389831 .

[11]. Where are Moon's Apogee and Perigee? Do they rotate too?. https://astronomy.stackexchange.com/questions/40681/.

[12]. Byblos. https://www.britannica.com/place/Byblos.